Page Contents

OVERVIEW

How could a tissue biopsy ever be misleading? Isn’t the point of taking a tissue biopsy completely grounded in the notion that it will clarify instead of confuse the clinical picture? Isn’t histology the best way to diagnose most anything that can have histology collected?

The case discussed on this page provides a great example of when a tissue biopsy can confuse the clinical picture, and actually put up obstacles with regards to providing the best care for the patient. A tissue biopsy on its own can be very useful, BUT it must be interpreted in the correct clinical context.

WHAT HAPPENED?

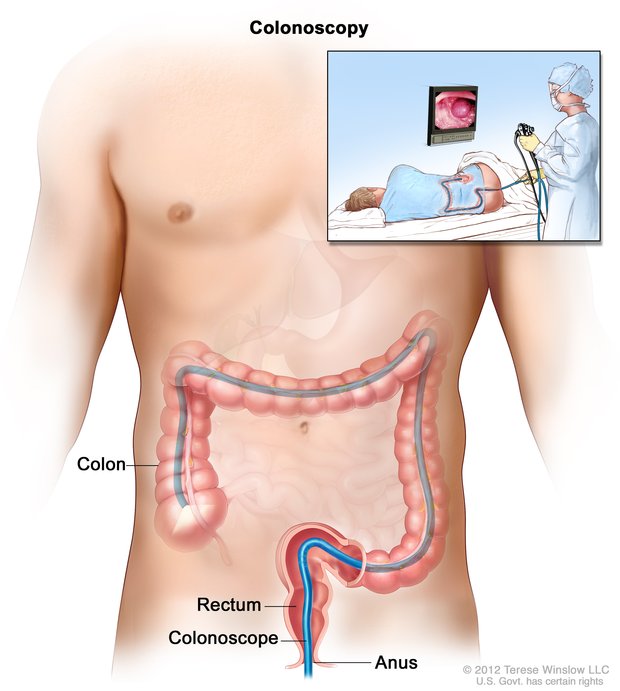

The patient in question is a 25 year old male who has no remarkable past medical history. He is admitted to the hospital with severe abdominal pain and is quickly found to have a large ileocecal mass. The patient is scheduled for a colonoscopy so that the mass can be biopsied prior to surgery.

Due to miscommunications between the surgical team and the GI physician conducting the procedure, the mass is not biopsied during the colonoscopy. At this point the patient’s scheduled surgery is upcoming, and the surgeon decides that an intra-operative biopsy will be conducted to inform how extensive of an operation will be conducted.

If the mass is not cancerous then the surgeon plans to resect a minimal amount of bowel (to preserve proper function of the GI tract).

If the mass is cancerous then the surgeon plans to resect a larger amount of the bowel to ensure that the malignancy is much less likely to recur in this young patient over his lifetime.

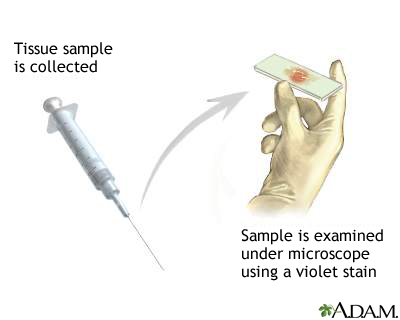

During the operation a sample of the tissue is sent for histological analysis. The surgeon waits for the results before completing the operation. Upon hearing that the biopsy is negative for any signs of cancer, the less extensive operation is completed. The entire large mass is sent for histological analysis and the patient recovers quickly from the surgery and is sent home.

A week after the patient is discharged from the hospital, the pathology results from the whole removed mass return. They show areas of malignancy (outside of the section biopsied during the operation). The patient is called back to the clinic and and told that it is recommended that he undergo a second procedure so that more of the bowels can be resected to lower his chance for cancer recurrence.

AT WHAT POINT DID THE FOREST BECOME LOST IN THE TREES?

It seems that the clinical utility of a tissue biopsy has eclipsed its limitations in this case. While it makes sense to modify the extent of the patient’s surgery based upon the nature of the tumor (i.e. cancer vs. not cancer) the concept of sampling error must be kept in mind with such a tissue biopsy. The patient’s mass was very large, so sending a small intraoperative tissue biopsy could very well MISS the presence of malignancy (which is exactly what happened in the case above). A biopsy really is a sample of the mass, and the larger the mass is in size, the more likely a small tissue biopsy may not represent the entire tissue accurately.

WHY SHOULD WE NOT THINK ITS COMPLETELY “CRAZY” THAT THIS HAPPENED?

On the surface of it all, it really is not that unreasonable that the situation above happened. A negative tissue biopsy often can give a false sense of security (especially if the concept of sampling error is not kept in mind). At the time of the operation, the surgeon had faith in the results of the biopsy, and legitimately believed that the patient’s mass was not cancerous.

WHO CARES? WHAT WAS THE HARM IN WHAT HAPPENED?

The end result of this was that the patient now (if they want to minimize cancer recurrence) will have to undergo an extra operation. This larger resection could have just been done during the initial operation and saved much trouble for everyone.

WHAT IS THE TEACHING POINT HERE? HOW DO WE AVOID THIS IN THE FUTURE?

At the end of the day, the base teaching point is understanding the limitations of a tissue biopsy. This case above begs the question exactly how would have the tissue biopsy results (either during the colonoscopy, or intraoperatively) changed the management of the patient? It seems that if either biopsy was positive for malignancy, then the larger operation would have been done regardless.

But what does a negative biopsy result in this context truly mean for the patient? As it was observed with the case above, a negative biopsy really does not rule out the possibility for malignancy. For this reason situations like the one above beg the question if the larger operation should be done in most circumstances (given the chance of missing cancer on any type of biopsy)? Or perhaps a more extensive intra-operative biopsy (the whole mass can be sent to pathology so it can be sectioned and areas of interest can be observed) can be taken to minimize the chances that malignancy may be overlooked?

While their are not always clear answers to these questions (there are more or less conservative approaches) perhaps the most universal take-away point here from this case is being aware of the limitation of a tissue biopsy, and communicating the risks of basing clinical decisions from these biopsy results to patients. No matter how hard we try in medicine, or what we decide, some mistakes will always be made. In the case above, if every patient has the larger operation (regardless of the biopsy results) a fraction of them will have an unnecessarily large operation (because their mass may be cancer free). Alternatively (as was seen with this case), if the negative biopsy is trusted, a fraction of patients will still turn out to have malignancy and will require a second operation.

Page Updated: 09.27.2016