Page Contents

WHAT IS IT?

Immune thrombocytopenic purpura/immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is an autoimmune condition by which antibodies bind common antigens (such as GPIIb/IIIa) on platelets leading to their destruction. Many cases are idiomatic (primary ITP), however certain disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus or antiphospholipid antibody syndrome can cause secondary ITP. Many drugs are associated with ITP (such as acetaminophen and aspirin) and even certain infection (such as HIV and hepatitis) have been linked to the condition.

WHY IS IT A PROBLEM?

Regardless of the initial cause, developing autoantibodies (ones that cause phagocytosis by macrophages) to platelets will lead to their destruction in the reticuloendothelial (spleen, bone, marrow, and liver) which will ultimately lead to low platelet counts in the body (thrombocytopenia). This will prolong patients to episodes of bleeding, given the important role of platelets in clot formation.

WHAT MAKES US SUSPECT IT?

Risk factors: young children (ages 1-7)

Common chief complaints: most patient complaints for this condition involve some type of issue relating to bleeding. These include:

- Excessive bleeding after trauma

- Menorrhagia (abnormally heavy bleeding during menstruation)

- Gastrointestinal bleeding (blood can be found in the stool or in vomit)

- Epistaxis (bleeding from the nose)

- Gum bleeding

- Hematuria (blood in the urine)

Skin: easy brushing, petechiae, or purpura (red marks on the skin caused by vascular bleeding).

HOW DO WE CONFIRM A DIAGNOSIS?

**Ultimately ITP is diagnosed based upon the presence of isolated thrombocytopenia: this means a low platelet count but no anemia (or anemia that is proportional to the amount of blood lost in the patient), normal white blood count (WBC), and normal peripheral blood smear.

Complete blood count (CBC): thrombocytopenia (platelet count < 100 X 10^9/L), normal WBC (3,500 to 10,500 cells/mcL)

Prolonged bleeding time (BT): patients with platelet issues will take longer to stop bleeding after a BT test is performed.

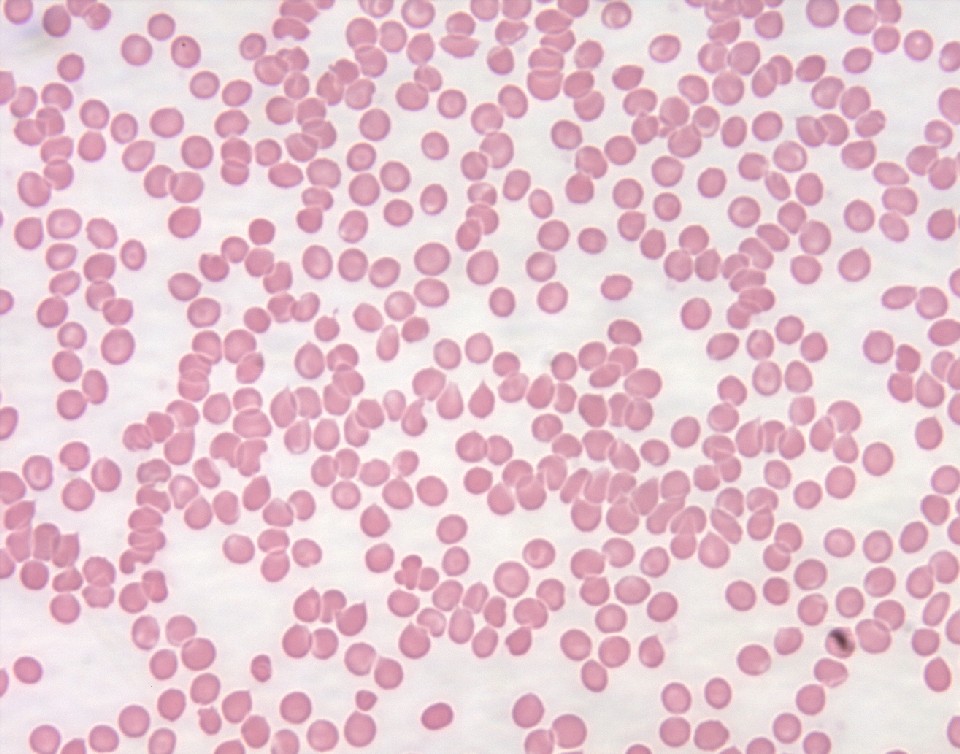

Blood smear: normal RBCs with no unusual findings suggestive of a different case of thrombocytopenia other than ITP.

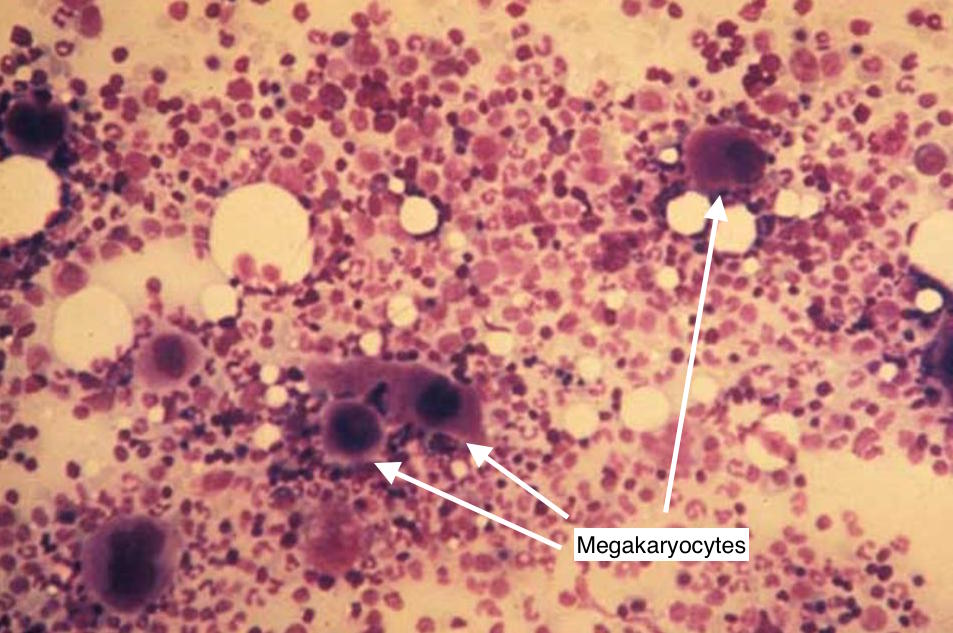

Bone marrow biopsy: if a bone marrow biopsy is conducted, one would expect to see increased presence of megakaryocytes (given that these are platelet pre-cursors that will compensate for ITP by trying to produce more platelets).

HOW DO WE TREAT IT?

*Treatment rarely indicated for platelet count > 50 X 10^9/L: exceptions include increased risk for bleeding or major surgery

**For secondary ITP treat the underlying condition

***Platelet transfusion may be required for emergency situations.

For Primary ITP:

First line therapy

- Corticosteroids (prednisone/dexamethasone): treatment has been reported to increase platelet counts (possibly indirectly though suppressing production of white blood cells in the bone marrow).

- IVIG (intravenous immune globin): this option is for patients who are bleeding, high risk for bleeding, unresponsive to steroids, or contraindicated for steroid use. Patients are given a large amount of many different antibodies found in normal serum, some of which are believed to inactivate autoantibodies (mechanistic details not completely understood).

- Anti-D immunoglobulin: this option is for patients who are bleeding, high risk for bleeding, unresponsive to steroids, or contraindicated for steroid use. This is an antibody against the Rho (D) immunoglobulin found on red blood cells. The mechanistic belief is that this antibody bids to Rh+ RBCs, saturating macrophages with opsonized RBCs (making it less likely that platelets will be phagocytize). Patients need to be Rh+ in order for this treatment to work.

Second line therapy

- Thrombopoietin (TPO) receptor agonists: these bind the TPO receptor and causes megakaryocytic growth and differentiation into platelets (which will increase the number of circulating platelets in the blood. Expensive treatment option!

- Rituximab: Monoclonal antibody that targets CD20 (found on B-cells). Ultimately can decrease autoantibody production by facilitation destruction of B-cells.

- Splenectomy is most successful treatment, but wait ≥ 6 months due to chance of spontaneous remission. If considering splenectomy, with at least 6 months form time of diagnosis due to possibility of spontaneous remission.

HOW WELL DO THE PATIENTS DO?

Adults who present with this condition generally have gradual onset with a chronic course of disease, however children often have spontaneous remission after 6 months (source)

WAS THERE A WAY TO PREVENT IT?

There are not clear methods of prevention this condone.

WHAT ELSE ARE WE WORRIED ABOUT?

Any type of bleeding! Perhaps an obvious statement but do not overlook this risk in patients who present to you with severe thrombocytopenia.

OTHER HY FACTS?

Prothrombin (PT) and partial thromboplastin times will be normal (coagulation factors are not effected).

ARCHIVE OF STANDARDIZED EXAM QUESTIONS

This archive compiles standardized exam questions that relate to this topic.

Page Updated: 01.09.2016