Page Contents

- 1 OVERVIEW

- 2 WHAT IS THE POINT OF THIS STUDY?

- 3 WHAT IS THE CLINICAL STRUGGLE?

- 4 WE HAVE ESTABLISHED THE PROBLEM, BUT WHAT IS THE SOLUTION?

- 5 WHAT TO DO: THE INTIAL CATEGORIZATION OF THE PATIENT

- 6 WHAT TO DO: WHAT ARE SOME CLEAR SIGNS THAT A CT SCAN IS INDICATED?

- 7 WHAT TO DO: CRITERIA TO RULE OUT THE NEED FOR A CT-SCAN

- 8 WHAT TO DO: PATEINTS WHERE THERE IS NO CLEAR RECOMMENDATION

- 9 IS THIS STUDY PERFECT?

OVERVIEW

The goal of this page is to take the landmark PECARN paper titled “Identification of children at very low risk of clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort study” (Kuppermann et al. 2009, The Lancet) and distill down its major takeaways for clinical practice.

TO THE READER WHO UNDERSTANDS THE PECARN STUDY AND JUST WANTES A QUICK RISK ASSESSMENT TOOL USE THE LINK HERE.

WHAT IS THE POINT OF THIS STUDY?

Characterizing pediatric head trauma: who needs a head CT?

This is the heart of the study: let us take a moment and very quickly summarize why this study was even done in the first place. Fundamentally, children commonly will experience head trauma (that can vary in severity). In most of these cases where a child has experienced head trauma, the evaluating physician will have to make a decision as to WHETHER OR NOT THE CHILD REQUIRES A HEAD CT SCAN. While there are some common sense elements that always go into decision making like this, this 2009 PECARN study helped to provide a very thorough evidence base to support a more clear and standardized decision making process when trying to assess if the child in question would benefit from receiving a CT scan.

WHAT IS THE CLINICAL STRUGGLE?

At a glance it may be hard to appreciate why this even is a difficult question: to try and explain why having a clear methodology for deciding who requires head CTs is important, let us take things to the EXTREMES!

What if we didn’t scan anyone?

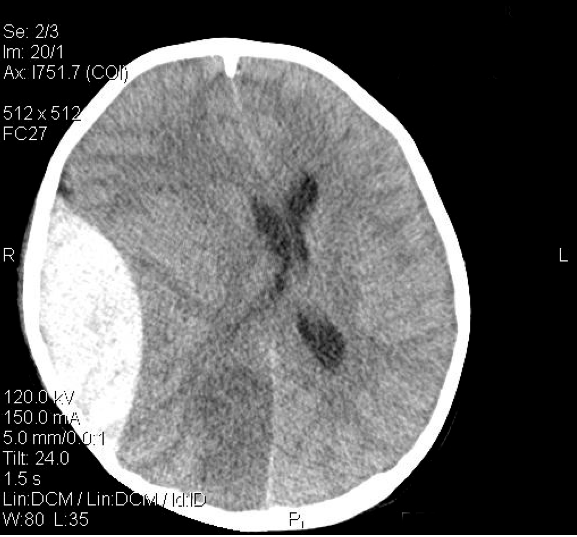

It is perhaps easier to appreciate the danger in not scanning any child with traumatic head injury. Simply put, if no child received head CT scans there would be certain instances where intracranial bleeding was not detected. And while not ALL blood in the cranium necessarily requires (or even has) a clinical intervention, there will be instances where patients will have severe morbidity or mortality that could have been avoided by gaining a CT scan.

OK, so what if we scan everyone?

Even after factoring out the cost and logistical obstacles that scanning every child with a head injury cause, there is a very important consideration that should not be overlooked. A CT scan will expose the scanned child to X-ray radiation, which very likely increases the chance of developing malignancy later in life. While the exact numbers are not clear (and studying this topic can be a nightmare), it is fairly safe to assume that exposure to CT scan levels of radiation does carry SOME risk of increasing malignancy. If every child with a head injury is scanned, then (however small) there will be instances where children will develop malignancy later in life due to receiving the scan. AGAIN, proving the casual link between this precise CT scan and the diagnosis of malignancy in specific cases is essentially impossible, however globally we can appreciate how this general statement can be made.

WE HAVE ESTABLISHED THE PROBLEM, BUT WHAT IS THE SOLUTION?

Fundamentally the solution here is figuring out a methodology that limits the number of unnecessary CT scans ordered on pediatric patients who have recently experienced head trauma. While there will always be instances where CT scans should have been ordered (but were not), in addition to situations where a CT scan was ordered but did not show any useful findings, we can work to MINIMIZE these cases. This again drives to the heart of this PECARN study, whose results will be applied practically below.

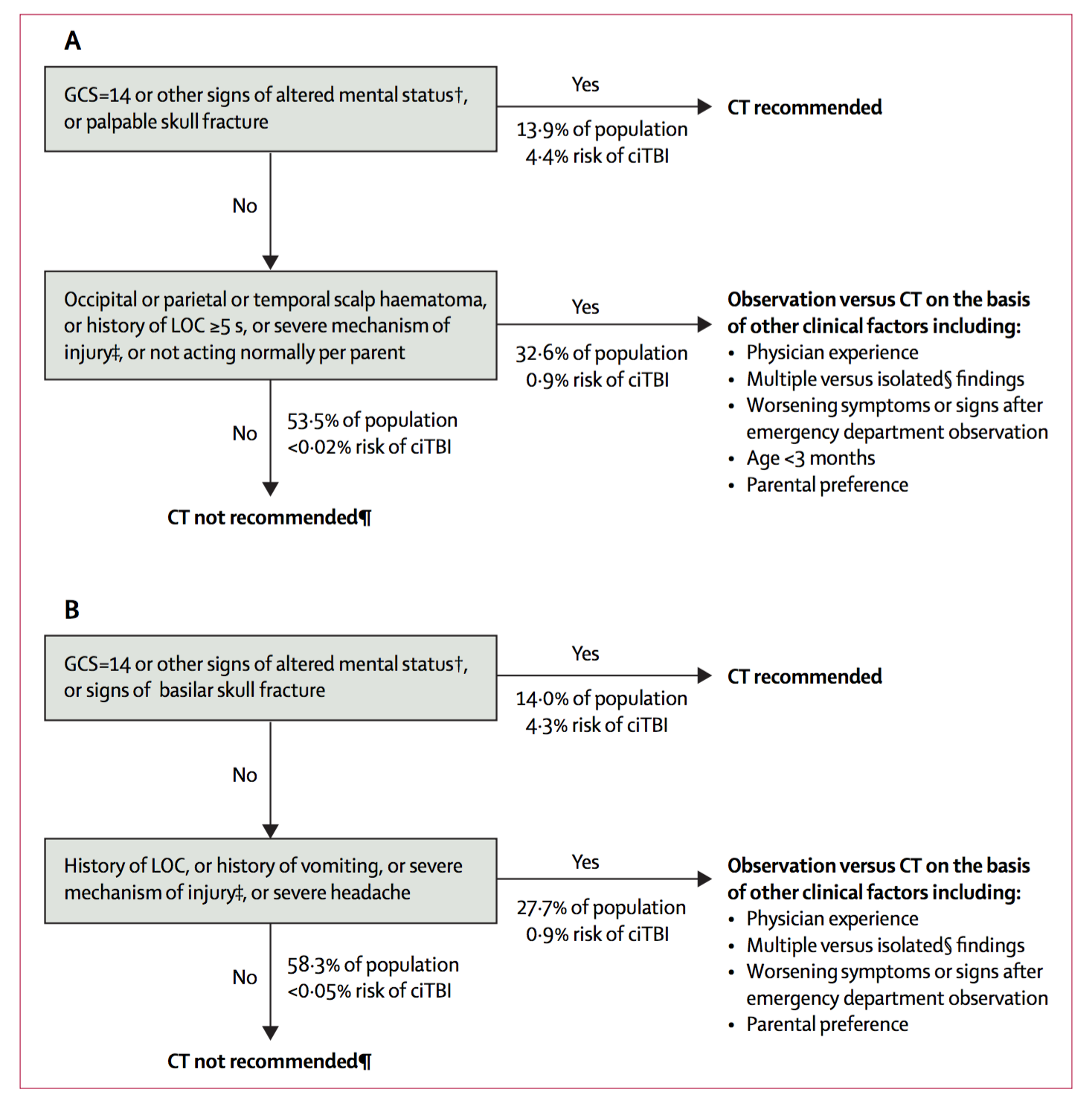

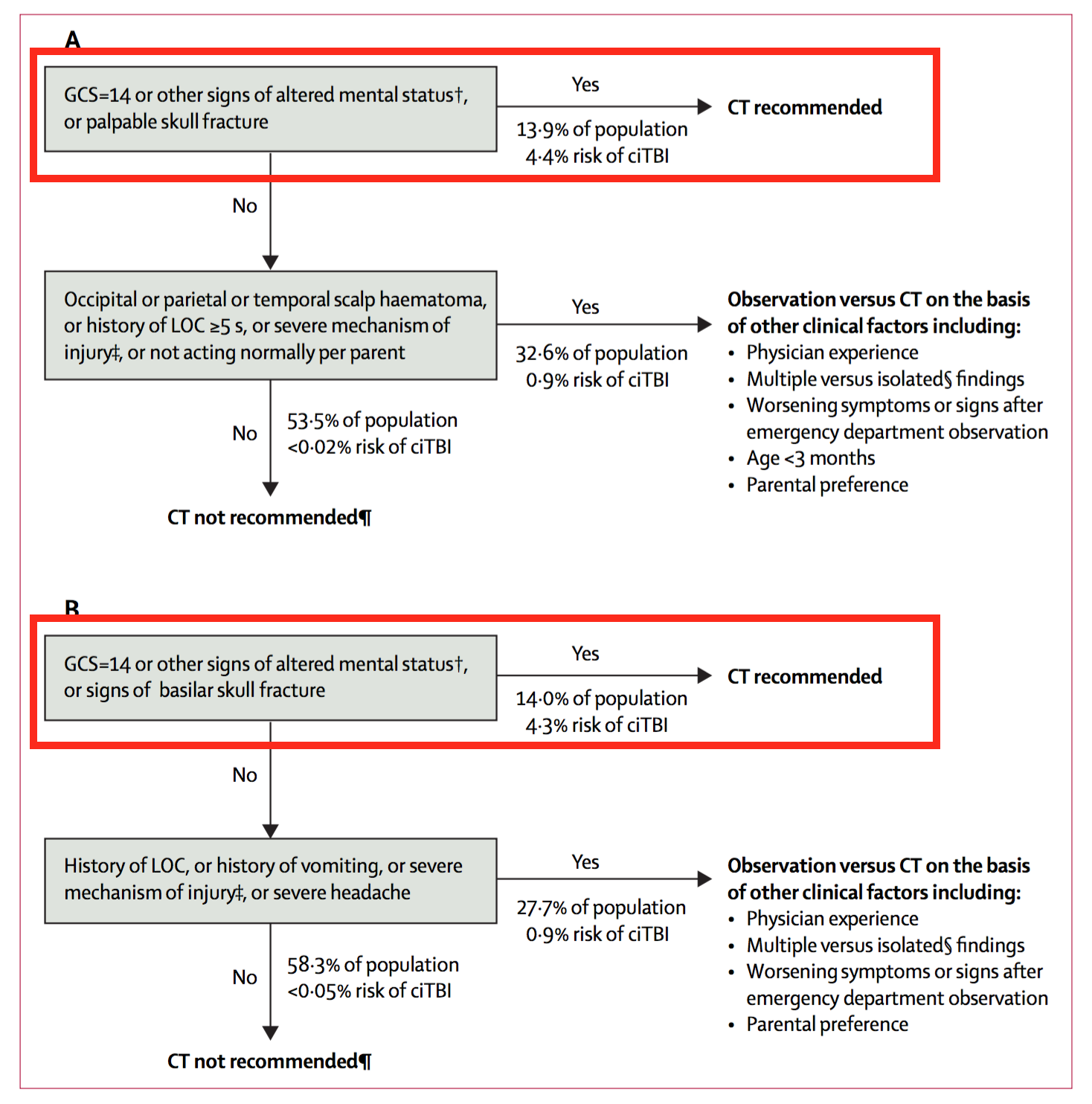

WHAT TO DO: THE INTIAL CATEGORIZATION OF THE PATIENT

Given our philosophical discussion above, let us get back to practical reality! We must take the results of this landmark publication and put the to good use in the clinic, so that we can provide value to our patients. Our first step will be categorizing our patients into 3 major groups.

Patients who “clearly” DO require a scan:

This patient population is listed first generally because it may be the most obvious. Typically in more obvious emergency situations (frank trauma, comatose patient) the patient will be rushed to get a scan (and this patient population was not studied in this paper).

Patients who “clearly” DO NOT require a scan:

Our next category involves patients that have experienced a very “trivial” fall. There will always be exceptions, and clinical judgment must constantly be used (ex. patients with a “low risk” fall may have focal neurological deficits on exam, and could still require image. Examples of these trivial falls include many types of ground level injuries such as:

- Running into a objects from ground level

- Falls from seated positions /walking/running

The chance of a CT scan providing value in these instances is so low, that justifying its usage (in the absence of a compelling history/physical) really cannot justify the risks of the scan. This patient population was also not studied in this paper.

Patients who MIGHT require a scan:

Now we are getting to the good part! This is the most difficult patient population to evaluate, and this category of patient requires the most evaluation in coming to a decision about whether or not a CT scan is required. This patient population was studied in the paper and here are some important criteria used for the study:

- Trauma that was more serious then the trivial falls outlined above

- No head trauma signs other then scalp abrasions/lesions

- No penetrating head trauma

The rest of this page will be dedicated to working up this patient population

WHAT TO DO: WHAT ARE SOME CLEAR SIGNS THAT A CT SCAN IS INDICATED?

Essentially, if any of the following is found in the patient, then based upon the PECARN research study, a CT scan should be ordered.

Imperfect Glasgow Coma Scale: the bottom line is that ANY SCORE BELOW 15 RESULTS IN A CT SCAN

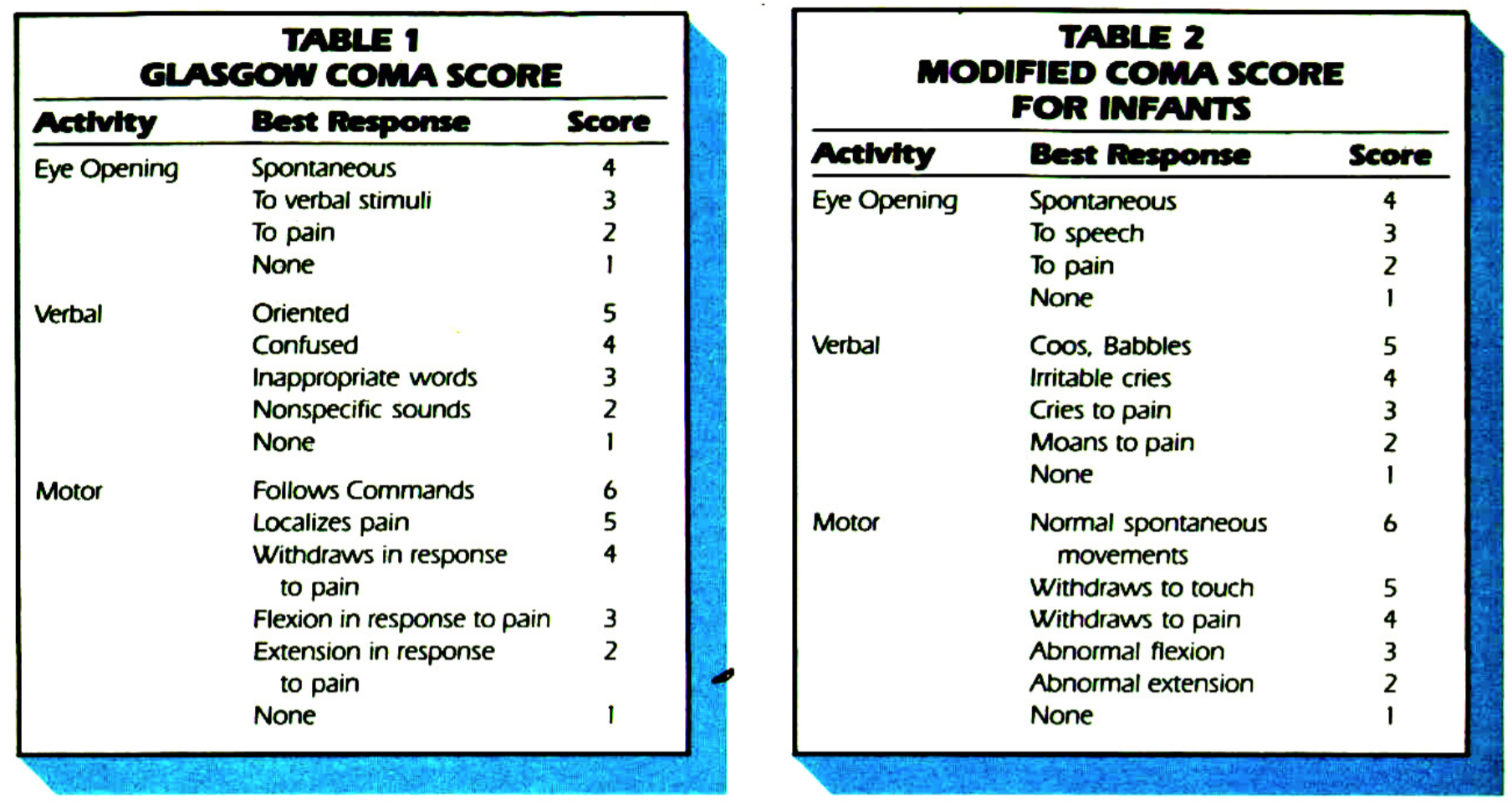

Our first step will be using this standardized clinical tool to assess for the patients mental status. This is a subjective scale (and many slightly varied versions exist in the world) so let us use the exact criterial used for the PECARN study for the sake of consistency.

Infants (under 2 years of age) vs. non-infants (2 years or older): the study cites this paper here for the infant GCS criteria and this one here for the non-infant GCS criteria. Both are shown in the figure below. It is important to note that for the infant scale, the nature of the child’s crying is subjective and the score given will depend on the physician (it is not clear in the study if this crying was consolable or non-consolable as this is very hard to actually record).

Other signs of altered mental status: these may be SUFFICIENT TO JUSTIFY A CT SCAN

Regardless of age: if the physician has a reasonable suspicion for consistent sings of altered mental status, this is enough (by the PECARN 2009 study results) to justify a CT scan. Examples of altered mental status include:

- Agitation,

- Somnolence,

- Repetitive questioning

- Slow response to verbal communication

Evidence of head fracture: the specifics vary based upon age group, however clear evidence of fracture IS ENOUGH TO JUSTIFY THE CT SCAN IN PATIENTS

Children younger then age 2: this patient population is recommended to receive a head CT if there is any palpable skull fracture.

Children age 2 or older: only signs of a basilar skull fracture will result in a recommendation for a head CT. These signs include:

- Retro-auricular bruising (Battles Sign)

- Periorbital bruising (raccoon eyes),

- Hemotympanum

- Cerebral spinal fluid otorrhoea,

- Cerebral spinal fluid rhinorrhoea

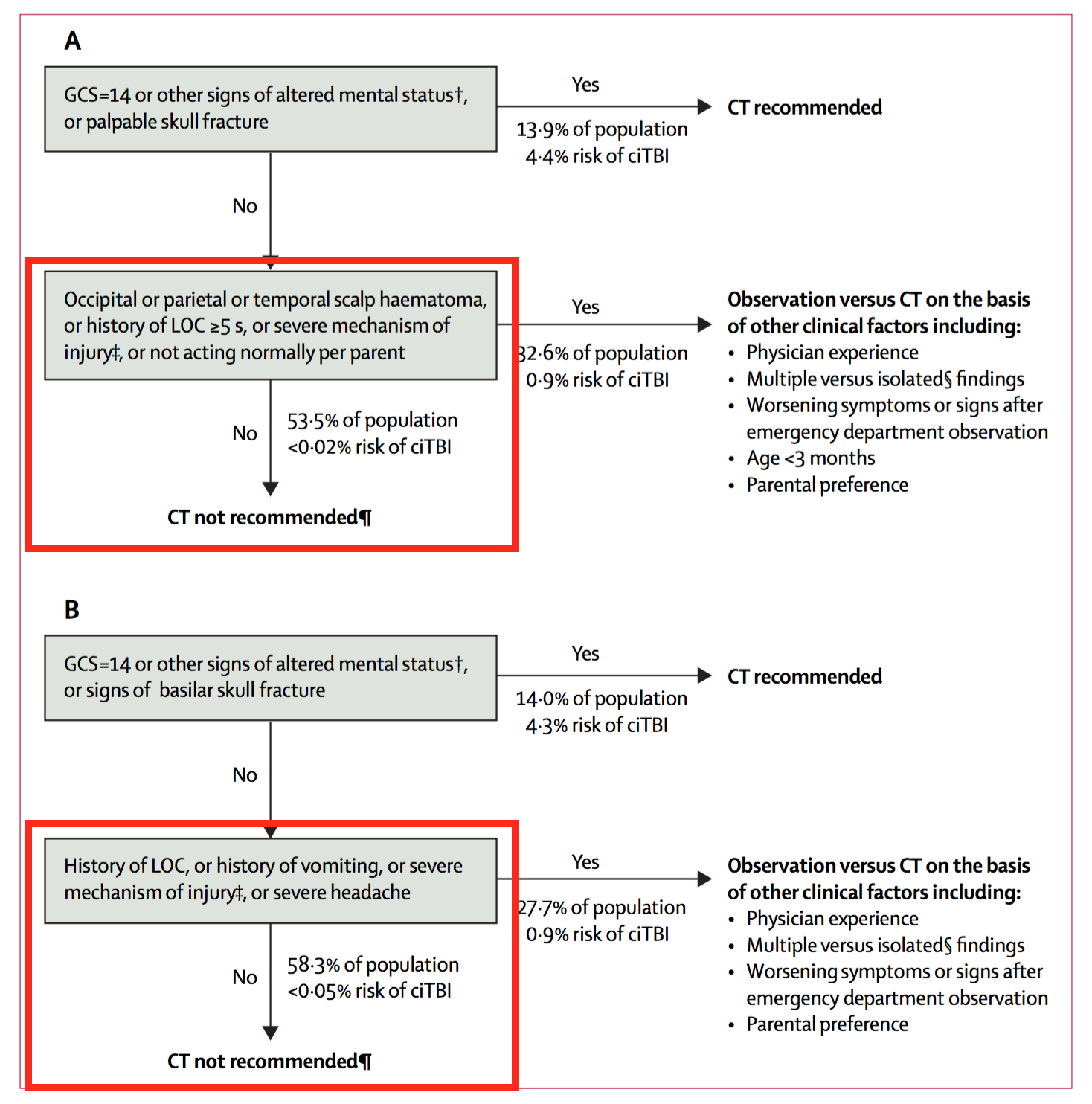

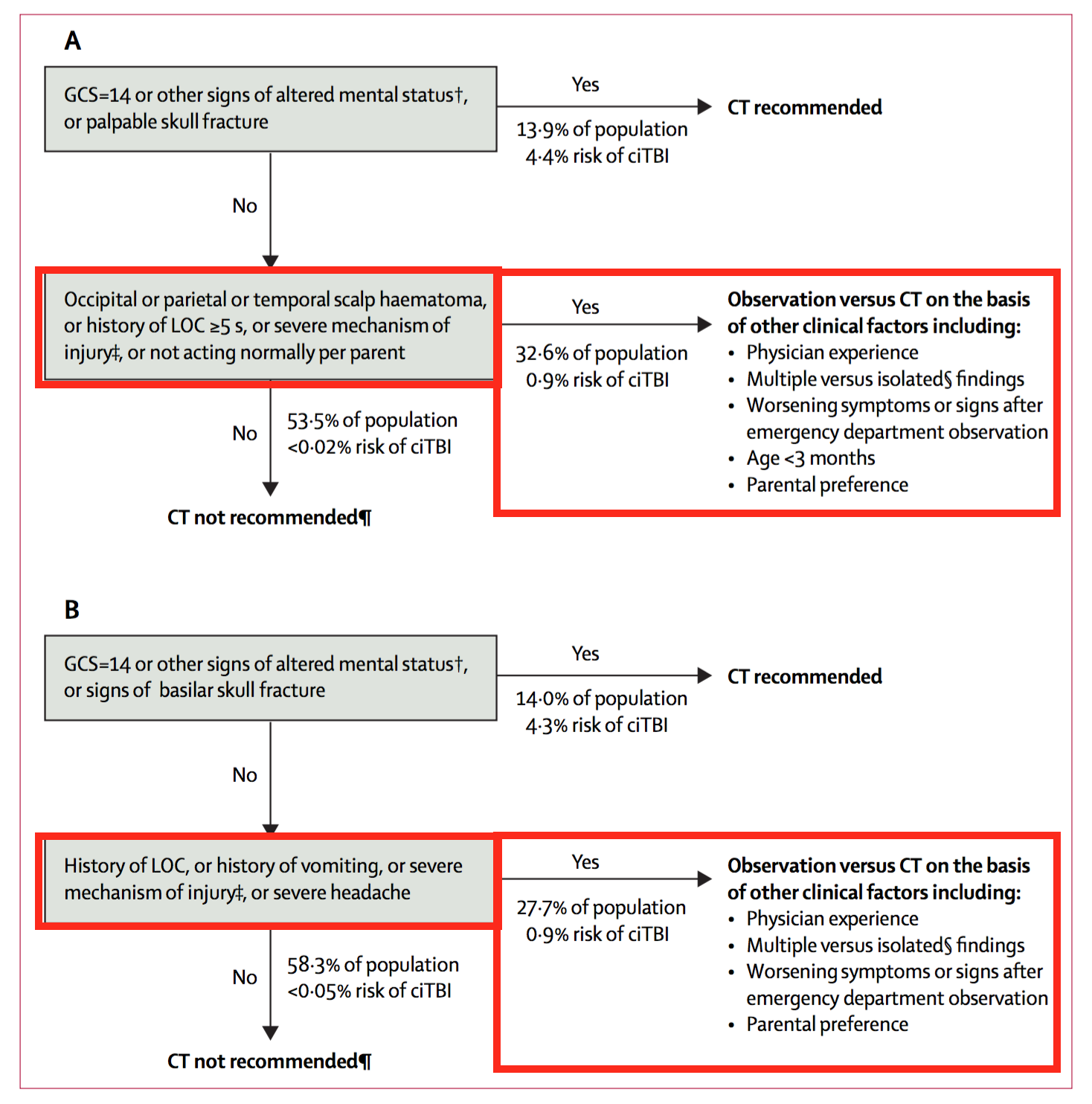

WHAT TO DO: CRITERIA TO RULE OUT THE NEED FOR A CT-SCAN

If the patient has a perfect GCS, no mental status changes, and no signs of skull fracture (above section) then our decision making requires another level of analysis (and becomes less clear). We must now identify a patient population that does NOT need a CT scan to help simplify things. If ALL following criteria are met, then based upon the study results a CT scan is not required.

No/short loss of consciousness: the nature of the timing depends on the age of the patient:

- Younger then 2 years old: patient must have no loss of consciousness or a loss less then 5 seconds.

- 2 years and older: patient must have no loss of consciousness.

No/severe mechanism of injury: in the study this term is defined as follows:

- Motor vehicle crash with patient ejection, death of another passenger, or rollover

- Pedestrian or bicyclist without helmet struck by a motorized vehicle

- Falls of more than 0·9 m (3 feet) or more than 1·5 m/5 feet for infants younger then 2 years of age

In young infants: patient acting normally per parent

In these young children the parents may be more able to notice changes to the child’s baseline. A CT scan can not be definitely ruled out as being necessary if the parents legitimately believe there are changes from the patient’s baseline.

In those 2 years or older: history of vomiting

This finding is more specific to older children (infants may vomit for other reasons) and its presence warrants further workup.

WHAT TO DO: PATEINTS WHERE THERE IS NO CLEAR RECOMMENDATION

If there are no clear signs to justify a choice one way or another (see above 2 sections) then things become even less clear. Patients are essentially in a state of “limbo” where they will be observed, and the decision to either get the scan or not becomes too nuanced to go over here in a clear fashion. The major elements of this observation will boil down to common sense. If a patient is clearly worsening then a scan could be indicated. If the patient remans stable (or even improves) it may be ok to send them home.

IT DEPENDS! Regardless of what is decided, informing the patient/parents of warning signs to look out for (essentially many of what was discussed on this page) is a worthwhile endeavor so that more vigilant eyes are evaluating the patient.

IS THIS STUDY PERFECT?

Of course not! Since it has been published an enormous amount of papers conducting sub-analysis have refined the results, however this paper itself is a great foundation to guide our clinal management. One should understand its basic algorithm without just blindly following it.

Page Updated: 08.04.2016