Page Contents

WHAT IS IT?

Cesarean delivery (i.e. C-section) refers to a surgical procedure where one or more abdominal incisions are made in order to delivery the fetus through the abdominal wall.

WHEN SHOULD WE DO IT?

There are very few absolute indications for a Cesarean. These include:

- Placenta previa

- Vasa previa

- Cord prolapse

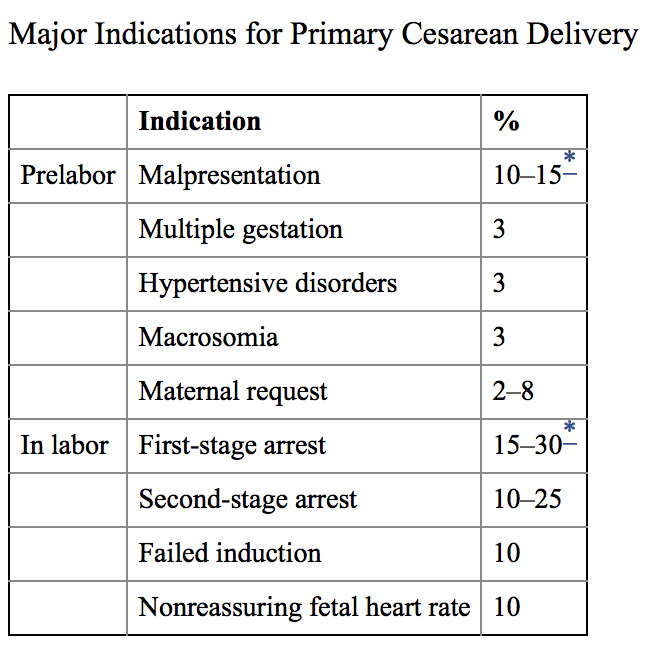

With this in mind there may be other indications for primary cesarean delivery (although some of these may be preventable).

Fetal intolerance of labor: while not necessarily a common occurrence, it is possible under certain circumstances that the nature of the mother’s contraction may not bode well for the fetus. This can be made evident with fetal heart monitoring/CTG. An example of this is when the contractions of the mother are so strong and rapid that the fetal hear rate decelerates for long periods of time (indicating extended periods of fetal hypoxia).

WHEN SHOULD WE AVOID IT?

When there is no accepted medical indication for the procedure.

HOW IS IT DONE?

While there can be variations with any procedure, the following are the general steps to a cesarean section.

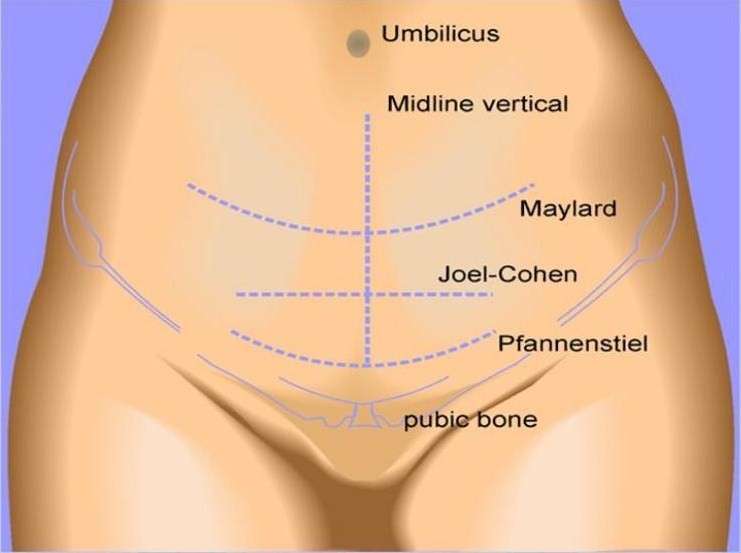

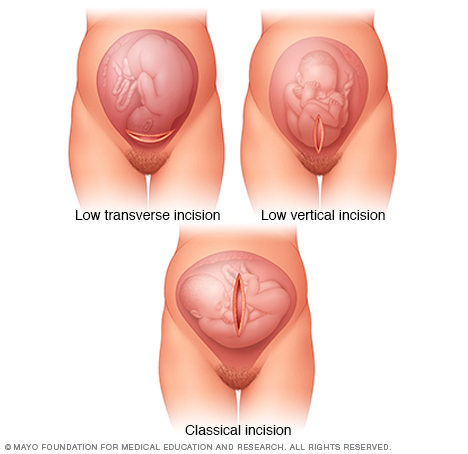

Abdominal Skin Incision: while this can either be transverse or vertical. Typically a transverse incision is made because it is associated with less postoperative pain, increased wound strength, and a better cosmetic outcome. A vertical incision is however faster for abdominal entry, and is typically reserved for instances where a quicker procedure is required (i.e. to save the fetus’ life). A scalpel can be used for this incision.

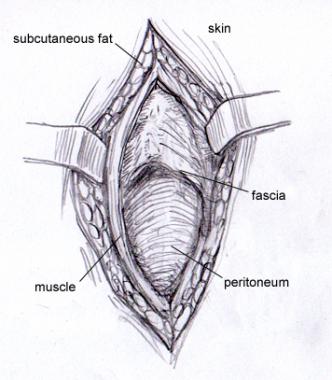

Opening the layers below the skin: once the initial skin incision is made, the following layers below the skin must be opened to gain access to the abdomen (in order from superficial to deep)

- Subcutaneous tissue layer: blunt dissection with fingers can be performed to reveal the rectus fascia beneath

- Fascial layer (rectus fascia/sheath): a small incision with a scalpel can be extended with scissors to expose the rectus muscles beneath

- Rectus muscle layer: can be separated bluntly to preserve muscle strength

- Parietal peritoneum: can be opened bluntly with fingers to reduce risk of damage to the bowel/bladder/etc. Keep in mind the bladder is near the uterus, and a bladder blade retractor is often used to keep the bladder away from the uterus. Commonly medical students scrubbed in on the surgery may be in charge of holding the bladder blade!

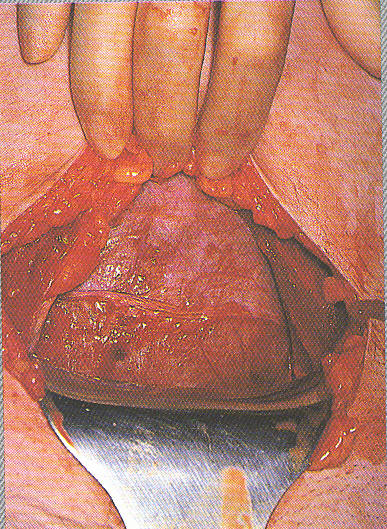

Removal of intraperitoneal adhesions/exposure of uterus: if there are any adhesions between the anterior abdominal wall and the anterior surface these should be dissected to allow for adequate exposure of the uterus. Blunt dissection can be performed (reserving sharp dissection only if needed). Once the uterus is properly exposed, it can be opened to allow for the delivery of the baby.

Opening of the visceral peritoneum on the uterus: it is important to note that a visceral layer of peritoneum covers the uterus that can be opened before an incision is made into the uterus itself. This is often done carefully with a scalpel.

Hysterotomy/uterus incision: Before any incision is made the surgeon should be aware of the general location of the placenta and the fetus. There are a few choices of incision type that will depend entirely on the location of the fetus/placenta. A lower transverse incision can be advantageous because it can lead to less blood loss, less need for bladder dissection, and a lower risk of rupture in subsequent pregnancies (source).

Fetal extraction: once the incision in the uterus has been made large enough, the fetus can be removed.

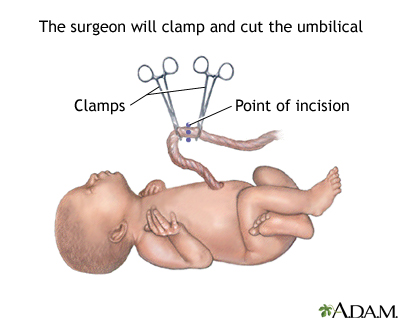

Cord clamping/inspection of baby: there is a bit of discussion about the best time-frame to clamp the umbilical cord (with some evidence showing benefit to delaying cord clamping). This will likely depend on the context of the delivery.

The umbilical cord is clamped in two places and cut before the rest of the procedure is completed.

Removal of the placenta: oxytocin can be used (but is not required) to promote uterine contraction, combined with the application of gentle tension on the umbilical cord to promote the explosion of the placenta (without requiring manual retrieval). The entire uterus is usually wiped with a gauge sponge too ensure that all the placental tissues are removed.

Postpartum hemorrhage prophylaxis: the uterus can be massaged as this point and oxytocin can be administered to help prevent postpartum hemorrhage and promote uterine contraction/involution.

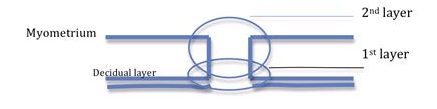

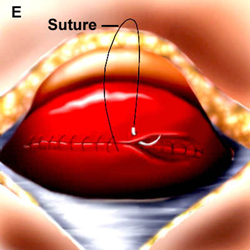

Uterine closure: the uterine incision must be closed. The uterus is usually exteriorized in order to make this process easier. The exact type of closure method used is controversial, however it seems that typically a double layer closure is used because it is associated with lower incidence of uterine rupture with subsequent pregnancies. This type of closure (as the name suggests) requires to layers of suturing:

- First layer: the first layer of suture (the endometrial layer) can be either a simple running suture or a running locked suture. The locked suture is more hemostatic and is used especially when there is evidence of arterial bleeding.

- Second layer: this overlaying layer (through the myometrium) should hide the first layer beneath it when it is closed. This is typically a simple running suture.

Fascia closure: the peritoneum layers and the rectus muscle are not usually closed. Instead the closing of the rectus fascia provides most of the wounds strength for the abdominal incision. This is often a simple running suture/continuous suture.

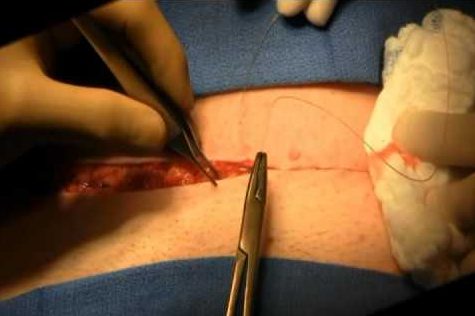

Closing of the skin: is the last step. A subcuticular suture method is used to minimize the scar that will remain from the procedure.

WHAT ARE SOME COMPLICATIONS?

Increased rate of maternal morbidity and mortality which can include:

- Postpartum bleeding

- Genital tract injury

- Infection

- Uterine rupture (especially with subsequent vaginal deliveries)

Increased complications in second delivery can occur when a patient’s first delivery was a Cesarean section.

Neonatal Respiratory Distress Syndrome (NRDS): This condition is caused by a deficiency in surfactant within the lungs. Neonates who undergo a cesarean delivery are at an increased risk for NRDS because they do not experience the same stress of vaginal delivery (thought to increase corticosteroids that stimulate surfactant production).

Increased risk of asthma and inflammatory bowel syndrome has been associated with children who were delivered via cesarean section (source).

**Just like all major surgeries, a Cesarean section carries the risk of infection, clot formation (possibly leading to a process like pulmonary embolism), and accidental damage to anatomical structures (such as the bladder).**

FURTHER READING

Preventing the First Cesarean Delivery

Page Updated: 07.09.2016